In February 2022, South Africa introduced the Climate Change Bill in parliament. If the bill becomes law, it will be the first legal framework in South Africa to respond to the climate crisis. But for climate policy to take effect, the public needs to be on board. A recent HSRC survey led by Dr Ben Roberts asked a series of interrelated questions to gauge the scope of South Africans’ knowledge of and attitudes towards climate change. By Andrea Teagle

The interior of Southern Africa is warming at around twice the global average. A report by climate change expert Prof Nicholas King focusing on the Western Cape, Limpopo and Mpumalanga predicts that in the coming decades the country will almost certainly experience extreme heat and weather events. South Africa can expect economic collapse, social conflict and displacement following coastal damage, food insecurity, water stress and disease outbreaks.

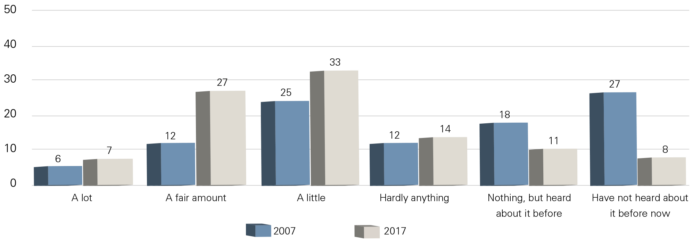

Such findings clearly point to the need for decisive action in all spheres of society to mitigate the climate crisis, particularly through reducing the use of fossil fuels. Yet, until recently, little was known about the attitudes and behaviours of South Africans in relation to the issue. Now, a report led by the HSRC’s Dr Ben Roberts has found that awareness of the climate crisis increased between 2007 and 2017, with the proportion of people who had never heard of the term ‘climate change’ dropping from 27% to just 8%.

“This positive shift [to more awareness] is likely to have been precipitated partly by increasing climatic shocks and media attention to the climate crisis,” Roberts observes. The study was commissioned by the Department of Science and Innovation (DSI) and National Research Foundation (NRF) and was included as a series of questions in the 2017 round of the HSRC’s South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS). It involved, in part, a replication of cross-national surveying undertaken by the European Social Survey (ESS) on this topic.

The findings show that while awareness of climate change had increased, most people still had only a shallow understanding of the issue: just a third of South Africans know at least a fair amount about climate change. (Figure 1.) The study also revealed a stubborn, significant minority of one in three who did not believe in the reality of climate change. In comparison, among European countries that took part in the parallel ESS survey at the same time, fewer than one in 10 participants held this view.

“We need to think about how best to tackle this scepticism,” Roberts says, adding that it matters because it affects pro-environmental norms and behaviour change.

Figure 1. Changes in self-rated climate change knowledge between 2007 and 2017 (%). Note: Item non-responses excluded from analysis

Source: HSRC SASAS 2017, DSI/NRF climate change and energy module

Urgent need for climate campaigns

The study makes use of Stern’s model of environmental behaviours, which traces links between what people believe and how they act. Specifically, it suggests that people will be more likely to act in environmentally friendly ways, firstly, if they believe in climate change, and secondly, if they believe that climate change poses a threat to things they value – clean air, wildlife, food and water security, for example. Finally, they must also believe that their actions can help to reduce the threat.

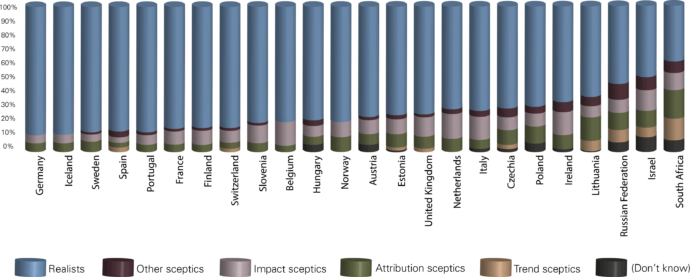

The study team identifies three types of climate sceptics: trend sceptics, attribution sceptics, and impact sceptics. Trend sceptics do not believe that the climate is changing; attribution sceptics dispute that people are to blame; and impact sceptics doubt the severity of the impact. ‘A majority of the South African population exhibited some form of scepticism on the issue of climate change. We found that only 39% of the adult population could be described as realists on the issue,’ they write. (Figure 2.) Similarly, a study led by Dr Nicholas Simpson that sought to measure climate change literacy across Africa, where literacy was defined as awareness of climate change and its anthropogenic causes, found average rates of 23% to 66% across 33 countries.

Roberts notes that greater knowledge about climate change does tend to reduce scepticism: “One of the silver lining messages from the study is that knowledge is not leading to greater ambivalence.” He recommends that South Africa rolls out robust climate crisis campaigns via different media and in different languages to sway hearts and minds in the green space.

Figure 2. Percentages of persons who are realists or exhibit some degree of scepticism on climate change

Comparatively high concern

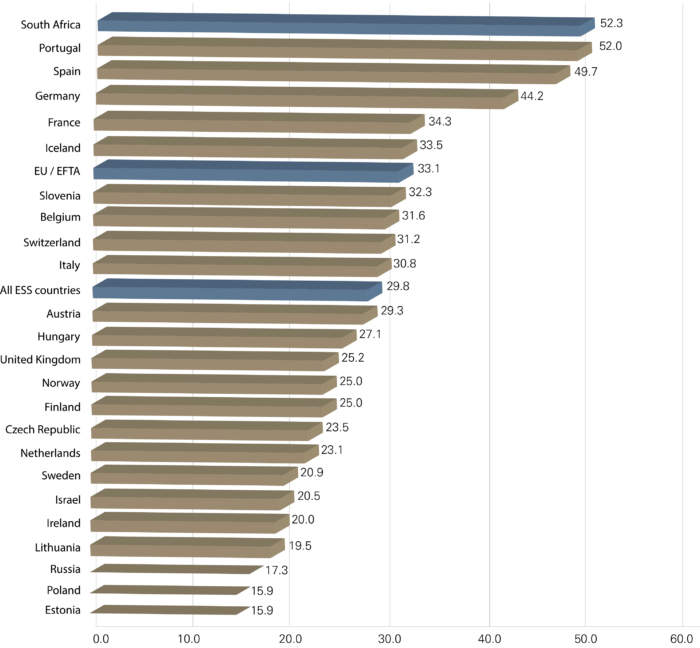

The second link in the model of pro-environmental behaviour is the belief in the impacts of climate change that you care about. The study suggests that among those who believe in the reality of climate change, concern is high (57%). In fact, South Africa’s levels of concern are higher than any country in Europe that undertook similar surveys. (Figure 3.)

The increase in concern corresponds with an upsurge in awareness of climate change, particularly among the black African majority. “Uncertainty has been replaced primarily with recognition of the far-reaching effects that climate change is going to have,” the authors write.

Figure 3. Concern about climate change in South Africa compared to Europe, ranked high to low based on the % that are very or extremely worried about it (2017). Note: Excludes non-responses as well as those saying that the climate is ‘definitely not changing’.

In a multivariate analysis, the study further confirmed that concern was linked to a higher probability of pro-environmental behaviour. This suggests that this worry can be built upon and leveraged to encourage behaviour changes such as lowering energy consumption.

Individual actions and systemic changes

The survey found that a substantial proportion of the South African public do believe they can reduce their energy consumption, but are less convinced that their actions will make a difference, or that enough people will change their behaviour to have any real impact. They are, however, more convinced of this than their European counterparts. Participants were asked to rate, on a scale of 0 (‘Not at all likely’) to 10 (‘Extremely likely’), how likely it was that limiting their energy would help reduce climate change, and the average South African score was 5.6. In comparison, of the 23 European countries that implemented the survey, all but Austria (with a mean score of 5) scored below 5, with Estonians (3.2) expressing the least confidence in personal efficacy.

Are those who believe that their actions can help to reduce the climate crisis right in thinking so? This question is often at the heart of discussions around how to respond to climate change.

Some activists worry that focusing on individual responsibility detracts from the larger, systemic issues driving the climate crisis, offloading responsibility from governments and industries. But individuals can play a role in holding the government and corporations to account, and pressuring them to follow through on climate commitments. According to Ben Roberts, the South African government has demonstrated the political will to shift towards a greener economy – for instance, by introducing the landmark Climate Change Bill.

Behaviour change at individual and household levels (lowering energy and water consumption, shifting to a plant-based diet, etc.) can help to reduce overall emissions, particularly among higher-income households, which are also better equipped to make lifestyle changes. As residents of the Western Cape demonstrated during the 2019 drought, when given the right information, people can come together to make pro-environmental choices. Aligning our actions with our values gives us a sense of agency and hope – both of which are critical to tackling the crisis.

Green energy transition

Recently, civil society groups wrote to the president demanding that the minister sign off on the construction of new renewable energy sources in response to the energy crisis. However, Roberts notes that a large share of the public is still supportive of coal-based energy supply. “Because of the level of poverty in South Africa, and the level of economic strain in recent years, people primarily want a reliable source of energy and one that’s relatively affordable – whether it’s coal or renewable energy,” he says. Gaining a better understanding of public sentiment is important to inform a just transition to a low-carbon, climate-resilient and sustainable society. Monitoring the public’s views on environmental issues is the focus of a new partnership with the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment, DSI, NRF, CSIR and the HSRC, he says.

Acknowledgement The research received financial support from the Department of Science and Innovation (DSI) and National Research Foundation (NRF) for fielding the climate change and energy module in the SASAS series, and the DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Human Development (University of the Witwatersrand) for analysis and publishing [grant SIP2020-CCHD-3].

Author: Andrea Teagle, a science writer in the HSRC’s Impact Centre

Researcher: Dr Ben Roberts is an acting strategic lead, research director and SASAS coordinator in the HSRC’s Developmental, Capable and Ethical State research division.