What impact would a universal basic income grant have on South Africa’s economy, and to what extent would it improve living standards? Debates on the potential developmental impact of a universal basic income grant (UBIG) often focus on these questions. The third UBIG webinar hosted by the HSRC, the Institute for Economic Justice and the Pay the Grants movement concentrated on the real or potential differences this type of grant could make to poverty, inequality, and unemployment. Matume Maila, Peter Jacobs and Asanda Ntunta share their thoughts.

In response to the COVID-19 socioeconomic crisis, many countries strengthened their social protection measures, often expanding the type of assistance that quickly reaches poor and vulnerable people in socioeconomic distress. Innovative social relief programmes, such as a universal basic income guarantee (UBIG), have also been considered or introduced in some countries. The South African authorities followed this global trend with its own safety net variants such as the social relief of distress (SRD) grant and targeted food assistance programmes. Invariably, the main motivation for these social assistance schemes was to make a visible and long-term positive difference to developmental outcomes for destitute individuals and families.

Evaluations of the developmental effects of social transfers have grown in volume globally, but the scientific rigour of these assessments has also been finetuned. Even if UBIG schemes are not mature enough for full impact assessments, lessons from comparable welfare interventions offer learnings that break new ground. In her presentation at the third UBIG webinar hosted by the HSRC, the Institute for Economic Justice and the Pay the Grants movement, Dr Kate Orkin, a senior research fellow at the Blavatnik School of Government in Oxford, shared insights from a large body of evaluations on the effects of cash grant programmes on long-term economic benefits. She said that donor agencies and governments base their investments in social grants on evidence from evaluations, hence their popularity. Empirical evidence indicates that a large proportion of the grant is used to purchase food, and significantly reduces hunger, especially child malnutrition. Orkin reported that “having a grant in the household is known to reduce secondary school dropout”. To support her main argument, Orkin also cited examples in which beneficiaries used the grant to invest in agricultural inputs for the sustainable expansion of agricultural output.

The social assistance interventions by the South African government in response to the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic were critical in assisting the vulnerable population to gain access to food, Matume Maila, a researcher at the HSRC, said at the webinar. Maila added that the provision of food parcels, SRD grants and other social programmes during the pandemic significantly reduced hunger and improved food security. International and local empirical evidence shows that cash transfer programmes have positive effects on the welfare of vulnerable populations. International evidence shows that emergency-type grants are important during economic shocks as they prevent the poor from sinking deeper into poverty. The rollout of social assistance during the pandemic was substantial, but the question is whether this should be expanded into UBIG, which is a universal intervention that provides permanent minimum benefits for everyone.

Ihsaan Bassier, a researcher affiliated to the Southern African Labour and Development Research Unit (SALDRU), traced the UBIG impact debate back to design and targeting questions. On average, a basic income grant premised on individual means testing (like the child support grant, social relief of distress or most basic income grant proposals) differs in its impacts from a family-based design.

Bassier’s impact framework questions the magnitude of the quantified impact: how large is the impact on the poverty gap and fiscal spending? A family poverty grant (FPG) targets all adults in poor households. If the FPG is set at R460 per month, which is below the food poverty line of R624, then it can potentially cut the poverty gap by 94%. By contrast, a basic income grant of R624 for all eligible people aged 18-59 reduces the poverty gap by roughly 52%. Moreover, the estimated cost of the FPG is in the order of R59bn per year, whereas the basic income grant is more than R200bn per year. The national treasury favours an FPG as a replacement for the COVID-19 SRD. But the FPG is politically divisive and costly as some SRD recipients will be excluded because they fall outside the targeted beneficiaries.

In theory, Bassier highlighted, the FPG is cost-efficient in reducing poverty levels compared to other policy options simulated in the study. He further reminded webinar participants that useful impact studies must also “take into account the second-order effects, which are the macro multipliers and local stimulus effects” that may pose additional estimation complexities.

Dr Asgahar Adelzadeh, chief economic modeler at Applied Development Research Solutions, explained at the webinar that a basic income grant is “a fiscally neutral pro-poor social policy” as it substantially cuts poverty and inequality without unsustainable increases in government spending. To arrive at this conclusion, Adelzadeh used a linked microeconomic-macroeconomic simulation model for South Africa. His modelled options start with a post-COVID-19 future without a basic income grant, called the ‘baseline scenario’. This baseline is then compared to simulated models with three versions of a basic income grant at different poverty lines: an unemployed, adult, or universal grant. The results of the model show that introducing a basic income grant would have a positive impact on economic growth. Furthermore, it would generate employment while also lowering income inequality and eradicating poverty in South Africa.

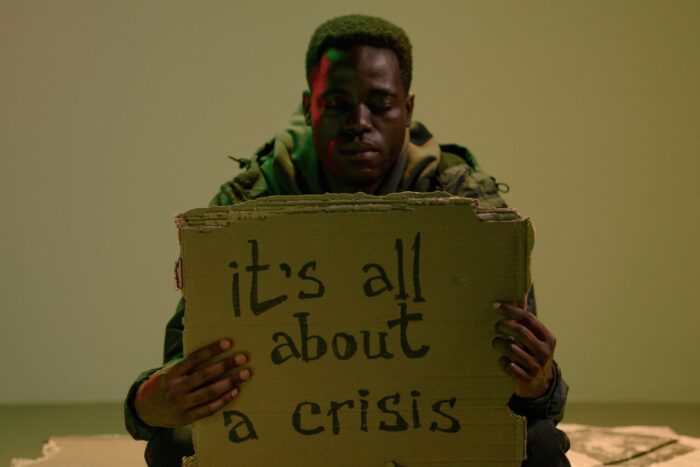

Shaeera Kalla, an activist at the Pay the Grants movement, brought a civil society angle to the conversation about the potential developmental impact of a UBIG. South Africa is grappling with several different crises, with about 24 million people depending on grants, she said. It is clear from the evidence presented by the speakers that the implementation of a basic income grant would have positive impacts on the economy. These insights must now be blended with more practical research about UBIG complementary interventions as it is not a silver bullet for impactful developmental outcomes. The challenges that the country faces highlight that we have a weak state and a weak civil society, said Kalla. Progressive civil society players should think about ways to overcome perception biases against the implementation of a basic income grant in the country, she added.

According to Adelzadeh, it is crucial to have a strategy that puts pressure on the post-1994 macro-economic policy framework in South Africa that is very conservative in its deliberations, with no space for effective discussion. It does not enhance economic growth, create jobs, or assist people to move out of poverty. Additionally, the framework is against social programmes that are expensive and helpful to the poor at the same time. Hence, society needs to become more active in pushing for policy revision.

Towards the end of 2021, the HSRC co-hosted, with the Institute for Economic Justice and the Pay the Grants movement, four poverty and inequality webinars on the UBIG debate. This overview is based on the third webinar under the title #BigQuestionsForUBIG: What is the impact?

Authors: Matume Maila, PhD research trainee, Dr Peter Jacobs, Strategic Lead: Changing Economics in the HSRC’s Inclusive Economic Development division, and Asanda Ntunta, junior analyst at the Competition Commission