A photographic exhibition reveals the mental health impact of #FeesMustFall protests

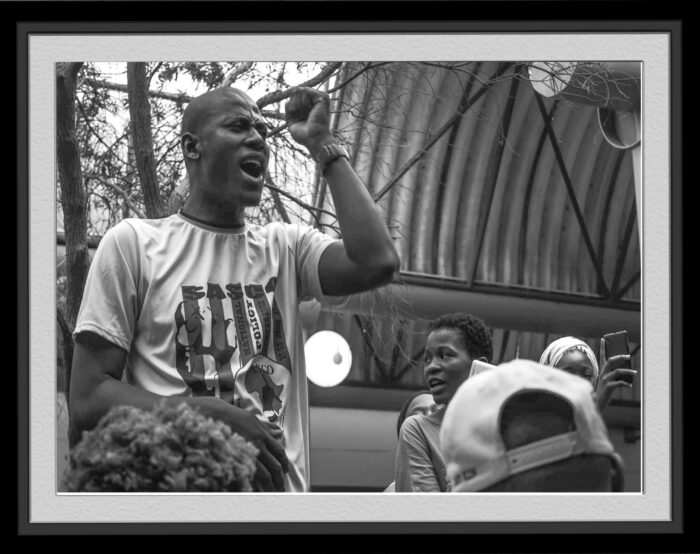

In 2019, HSRC researchers interviewed student activists from the 2015/16 university protests as part of a project looking at higher education governance and the problem of violent student protests. With student activists often depicted as either ‘heroic warriors’ battling against injustice or lazy or entitled ‘thugs’, the researchers were taken aback by what they found. The participants seemed vulnerable and deeply traumatised. Thierry Luescher spoke to Antoinette Oosthuizen about a photography project that gave these students a voice.

In the wake of the 2015/16 student protests at South African universities, a group of HSRC researchers and their colleagues became aware of an increasing incidence of trauma and mental health issues among students.

Working on an HSRC project funded by the Andrew W Mellon Foundation, Prof Thierry Luescher led a team of researchers looking into the South African student movement , focusing on higher education governance and the continuous and increasingly violent protests happening at universities at the time. “It was an archiving project, aimed at making sure that voices of student activists from that time were being recorded and archived,” says Luescher. “We don’t have that for events like the 1976 Soweto Uprising, for example.”

As he and his colleagues conducted interviews with former student activists from the movement, including the 2015 Rhodes Must Fall, Open Stellenbosch and #FeesMustFall protests, they witnessed strong emotional responses from participants.

Students would mention that they had never spoken about their experiences in that way before. “Recognising the presence of unresolved psychological issues, I realised that a space was needed where students felt safe and supported to talk about their experiences of violence and well-being. We needed to have professionals with counselling and psychological training, and we needed to find a suitable method for these former activists to express themselves,” Luescher explains.

He teamed up with Dr Angelina Wilson Fadiji, a psychologist and academic, and Dr Keamogetse Morwe, an expert in the study of student movements, violent protests and youth development. He also consulted with Tshepang Mahlatsi, a former student leader and student mental health activist. Building on the existing archival project, the HSRC researchers applied to the National Research Foundation for funding to do a photovoice project focused on violence and well-being. One of the outputs is a photographic exhibition, Aftermath: Violence and Well-being in the Context of the Student Movement, a collection of 34 images through which student leaders represent their experiences of violence and their search for well-being after the student protests.

Durban University of Technology

Why photovoice?

Due to language, educational, class or cultural barriers, people often struggle to articulate their concerns in such a way that political role players listen to them. Photovoice is a participatory research method that helps members of a community tell their stories through photographs. In 2019/20, the researchers held workshops with 26 student leaders and activists at the University of the Western Cape, University of Venda, University of the Free State, University of Fort Hare and Durban University of Technology[AO3] . These campuses had experienced high levels of violence during the 2015/16 #FeesMustFall student movements but had very little media attention.

Themes of violence

“We asked the former student activists about their exposure to violence, whether as perpetrators of violence, victims or bystanders,” Luescher explains. “We conceptualised violence in a very traditional sense but, for the students, violence also involved symbolic violence, structural violence, and various kinds of violations of their rights and dignity.”

In addition to protest and physical violence, the students’ experiences of violence could be grouped in themes including oppressive spaces, patriarchy, fear and trauma. For example, Kamohelo Maphike, a student from the University of the Free State, brought a photograph of the statue of Marthinus Steyn, describing it as a reminder of ‘racist Afrikaner nationalism’ at that university, as ‘a violent articulation’ of this university space ‘not meant for people of colour’.

An image of an academic transcript showed how a student had passed their first year with distinction, followed by an incomplete pass in their second year and a third year full of uncompleted modules and fails. The student described this as ‘the impact of systemic violence’ that was psychological and long term.

“It was one of my favourite pictures because it showed the link in the higher education space between exposure to violence, impact on well-being and eventually impact on learning,” says Luescher, who felt touched by the caption ‘Here lies the remains of what could have been a brilliant future’.

On judgement, objectivity and reflection

At the time of conceptualising the project, prominent academics and university leaders published their reflections on the student protests. From their standpoints, theirs were legitimate reflections, even though they typically excluded the voices of student activists.

“If you have been a vice-chancellor on a campus like Free State or Wits – even if you try to be as critical and scholarly as you can – you are not a disinterested observer. You were involved and might want to make yourself look good rather than admit to management mistakes,” says Luescher.

“However, we were not there to pass any judgment, whether on student activists, management, the police, or security personnel. Our purpose was to provide a platform for the voices of the activists.”

Another interesting perspective came from the Fort Hare postgraduate student and rugby coach Madoda Ludidi, who submitted a picture of himself standing at a rugby field. “He described rugby as a game of ‘structured violence’.” Alluding to the unpredictable nature of violence during student protests, Ludidi said, ‘On the field, there are rules that clearly structure the exertion of violence. Here, as a rugby coach, I am in control of the violence on the field.’ After he had encountered protest violence, the rugby field became a therapeutic space for him.

Responses to exhibition

The photographic exhibition is available online and has been taken to several universities, also virtually during lockdown. “Every time the students have been part of it. They co-own the exhibition and contribute to the resulting publications,” says Luescher.

The aim of the exhibition is to raise awareness – especially among university leaders and policymakers – about the impact of high levels of campus violence on student well-being. The student activists hope that this will lead to their grievances being taken seriously without the need for protests, and that campus counselling services to support students with mental health issues will improve.

“The exhibition’s value is that it starts conversations between members of the university communities. Rekgotsofetse Chikane, himself a student activist at the time, wrote a beautiful book, Breaking a Rainbow, Building a Nation. When we interviewed him about the future of the university in Africa, he said we need to have difficult political conversations and they need to be inclusive of all the stakeholders,” says Luescher.

“Without these conversations, politics will not change. The backgrounds of first-generation students can be so different from those of academics. They really don’t know much of each other.”

A frequent response from visitors to the exhibition was that they did not realise the extent of violence, and how students experienced psychological trauma. Many students and staff members also expressed the need to tell their own stories.

The next steps

The researchers continue publishing about this project, for example on the photovoice methodology and on ways of preventing violence and restoring well-being in a practical manual for student affairs staff and student leaders. A wider collection with more than 100 pictures and student narratives has been published in #FeesMustFall and its Aftermath: Violence, Well-being and the South African Student Movement (HSRC Press, October 2022).

Author: Antoinette Oosthuizen, a science writer in the HSRC’s Impact Centre

Contact: Thierry Luescher is a National Research Foundation-rated political scientist with expertise and research interests in the politics, polity and policy of higher education. He is the strategic lead of research into equitable education in the HSRC’s Inclusive Economic Development division. Luescher is also an adjunct professor at Nelson Mandela University and a research fellow at the University of the Free State.