Access to and enjoyment of natural resources (for example, good quality air to breathe, clean water to drink and fertile soil to produce food) enable us to meet basic human needs. These environmental resources are also needed for the achievement of other ‘non-basic’ needs, such as dignity and personal, social, economic and political wellbeing. With the terrible state of the air we breathe and the water we drink, one hopes that it is not too late to respect, promote, protect and fulfil the environmental rights enshrined in section 24 of our 30-year-old democratic Constitution. By Narnia Bohler-Muller, Yul Derek Davids, Ben Roberts and Gary Pienaar

This article is a summary of chapter 2 of State of the Nation: Quality of Life and Wellbeing, to be launched on 14 May 2024.

Photo by Sipho Ndebele on Unsplash

Healthy environment, healthy humans

Improved scientific understanding of human–environment interactions has led to a growing appreciation of humanity’s reliance on a healthy environment.

Access to and enjoyment of natural resources (for example, good quality air to breathe, clean water to drink and fertile soil to produce food) enable us to meet basic human needs. These environmental resources are also needed for the achievement of other ‘non-basic’ needs, such as dignity, and personal, social, economic and political wellbeing.

The right to a healthy environment and the concept of wellbeing are found in section 24(a) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa –

‘[E]veryone has the right … to an environment that is not harmful to their health or wellbeing’.

The presence of references to the environment, health and wellbeing in this section raises questions about the nature and meaning of the intersections between them. For example, human health and wellbeing are influenced both positively and negatively by environmental conditions, with significant economic, social and political implications.

The air that we breathe

Air pollution severely affects the health, wellbeing and human rights of the world’s population, with the poor living in hazardous areas rendering them particularly vulnerable. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), every year around 7 million premature deaths are attributable to air pollution globally. Overall, air pollution is responsible for more deaths than many other risk factors, including malnutrition, alcohol use and physical inactivity. Air pollution, including that derived from coal, affects everyone, but it harms poor populations the most. Typically, poor people are more exposed to air pollution, partly because they live or work close to industrial sites, power stations, coal mines and other sources of air pollution because accommodation in these areas tends to be more affordable.

The poor are also more susceptible to the health impacts of bad-quality air because of their limited access to health services. Approximately 98% of cities in low- and middle-income countries do not meet the WHO’s air pollution guidelines, compared to 55% in high-income countries. Reducing outdoor air pollution – by shutting down coal plants and replacing them with cleaner energy sources (solar, wind) – can therefore help to reduce the health and related inequalities caused by air pollution.

The UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment reports that fine particulate air pollution is the single highest environmental threat to health across the world. The UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights points to the increased risk of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, infections, heart disease, strokes, lung cancer, as well as pre-term births and low birth weight. It reports on a growing body of evidence that links air pollution to other illnesses, such as cataracts, ear infections, asthma in children, chronic deficits in lung function, childhood obesity, stunting, diabetes, poor cognitive development, lower intelligence and neurological disorders afflicting both children and adults. Children are particularly vulnerable to the negative impacts of poor air quality.

Intersectionality between the climate, the environment, health and wellbeing

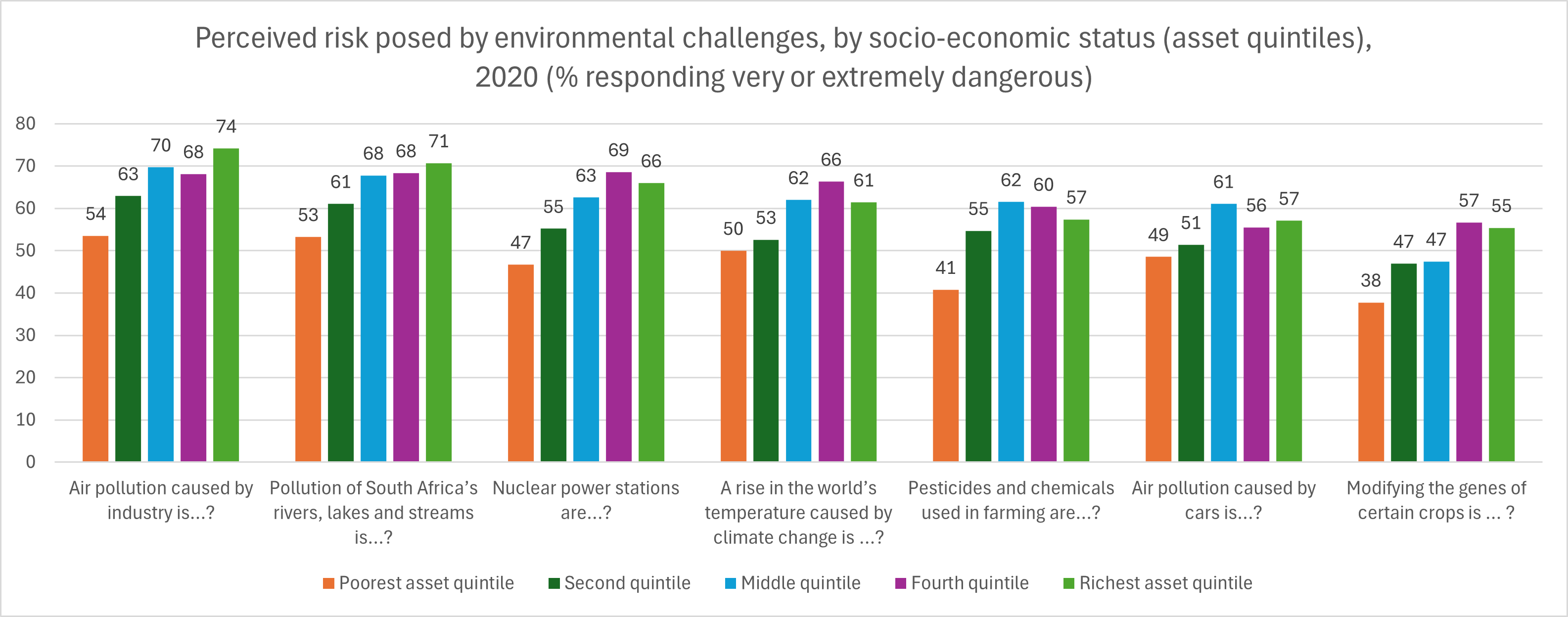

Public awareness in South Africa of these interlinkages is shown in the 2020 South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS), in which more than 50% of respondents indicated that they perceived air pollution, pollution of the country’s rivers, lakes and streams, nuclear power stations, climate change, and pesticides and chemicals used in farming as ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ dangerous to the environment (Figure 1). The 2020 SASAS survey also reveals that perceived risk posed by different environmental problems increased consistently as the socioeconomic status (SES) of respondents rose, suggesting that there was likely to be an educational or awareness effect underlying this perceived risk measure.

Figure 1: Perceived risk posed by environmental challenges, by socio-economic status (asset quintiles), (% responding very or extremely dangerous) Source: SASAS 2020

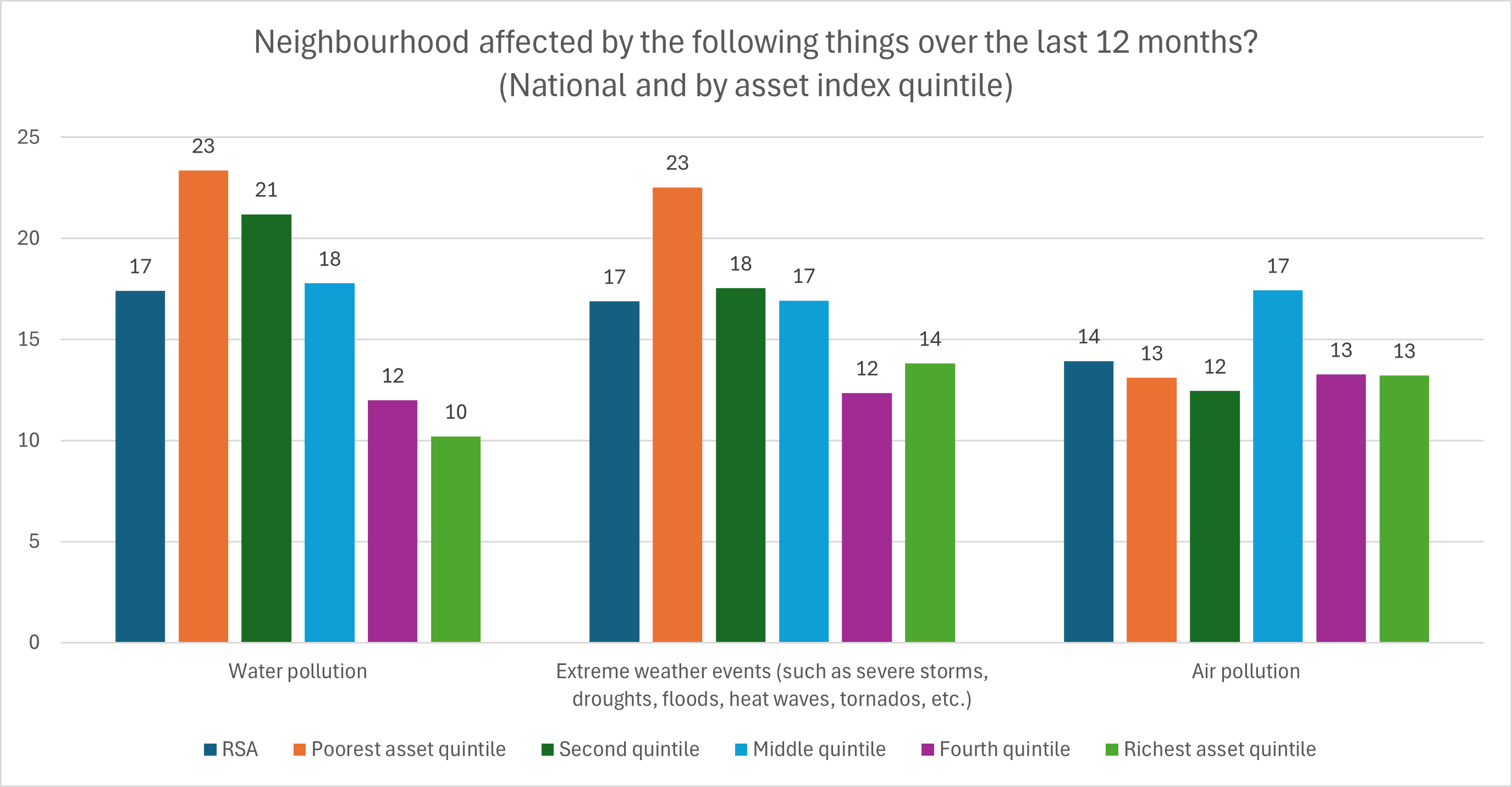

SASAS 2020 data showed that about 14% of South Africans believed that their local neighbourhood was affected to a great extent by air pollution, and 17% felt that water pollution and extreme weather events affected their local neighbourhood (Figure 2). The 2020 survey also shows that living in a neighbourhood that was recently affected by water pollution and extreme weather events was more common among those in the lower SES categories. The survey brought to the fore the dire straits of water scarcity and other pollution affecting South Africans.

Figure 2: Neighbourhood affected by the following things over the last 12 months? (National and by asset index quintile) Source: SASAS 2020

The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports dire implications of high levels of air pollution for the world’s poor. In addition, global warming and associated loss of biodiversity will severely impede progress towards each of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

Poor air quality in South Africa

South Africa relies on coal for more than 80% of its electricity and on fossil fuels for more than 90% of its energy.

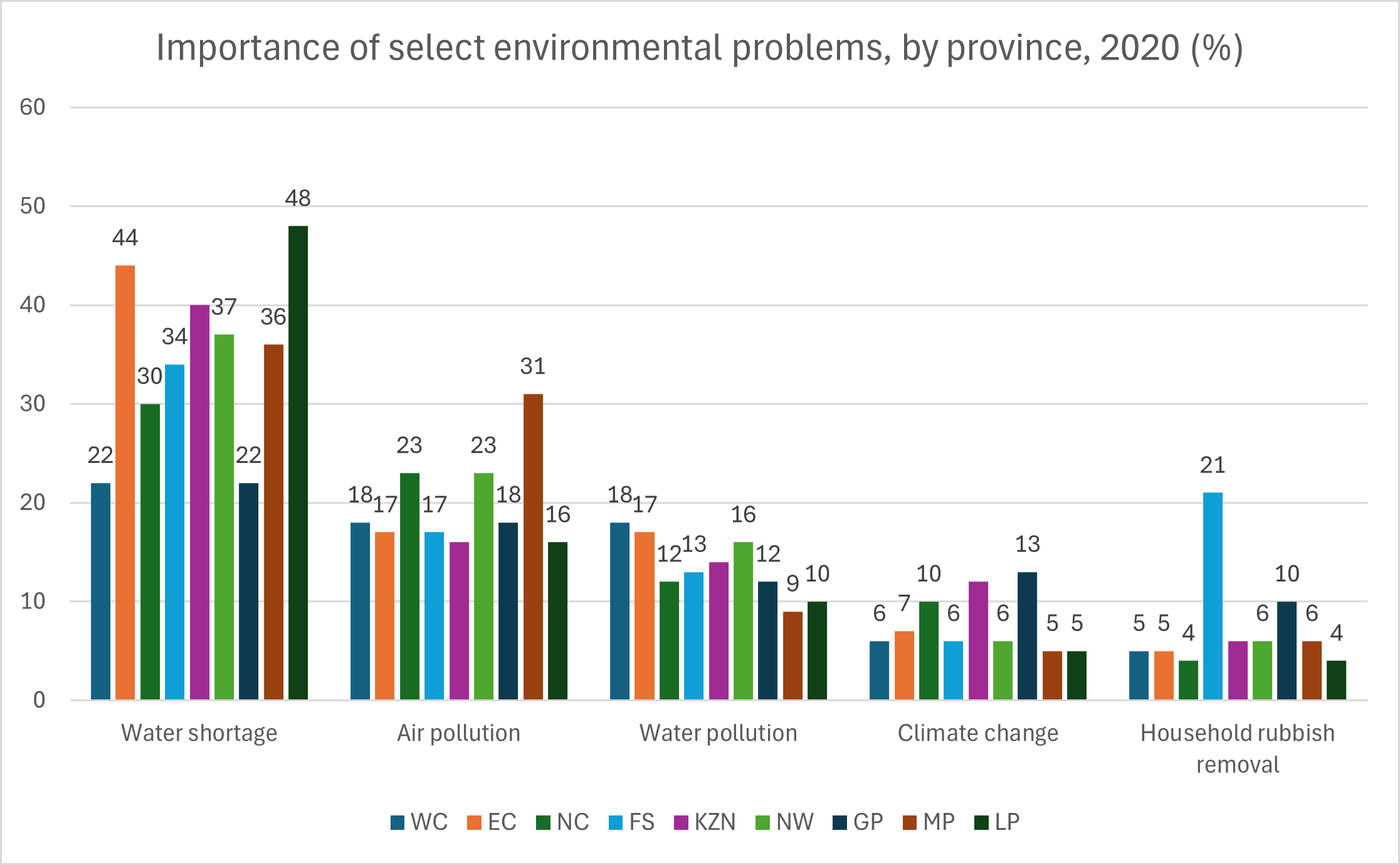

The provinces of Mpumalanga and Gauteng are two of the most densely populated areas of the country. Located close to Gauteng, Mpumalanga and Limpopo have the country’s largest coal-fired power stations and as such experience a high level of exposure to air pollution (Figure 3). A 2019 study commissioned by Greenpeace India found that Kriel in Mpumalanga, with its high concentration of coal-fired power stations, ranks as the second-worst SO2 emission hotspot in the world. A 2019 assessment by the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment found that approximately 5 000 people die prematurely each year on the Mpumalanga highveld from air pollution.

Figure 3: Importance of select environmental problems, by province, (%) Source: SASAS, 2020

South Africa’s National Framework for Air Quality Management, developed in terms of the National Environmental Management: Air Quality Act 39 of 2004, declares in its ministerial foreword that it is ‘the first national plan to clear our skies of pollution and ensure ambient air that is not harmful to health and wellbeing’. South Africa’s commitments in terms of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the 2015 Paris Agreement require us to set measurable targets to limit global warming to well below 2 °C, ideally 1.5 °C.

However, one of the reasons for a series of recent court cases brought by civil society organisations, such as Earthlife Africa and groundWork, is that the government’s improvement plans have not been undertaken expeditiously or consistently. For instance, Eskom has fallen behind the extended deadline for the installation of flue gas desulphurisation (FGD) technology applicable to the 4 800 MW coal-fired mega-power station Medupi in Limpopo. ‘Eskom has failed to install [FGD] technology, commonly known as air scrubbers, which scrub the fumes from the station of some of the sulphur dioxide (SO2) that is emitted.’ If Medupi runs at full capacity, without the FGD technology, it could lead to about 90 deaths every year. It is expected that Medupi will run without FGD for at least a decade. Reportedly, ‘more than 2 000 people have died over the years from illnesses caused by pollution from Eskom’s coal fleet, at a cost of around R30bn to the economy’, while Medupi has killed about 364 people each year.

The National Climate Change Response White Paper declares that South Africa’s health sector is one of the government’s five key priorities. It acknowledges that extreme weather events and increased climate variability associated with climate change significantly compound the negative effects on the health and resilience of vulnerable communities.

Conclusion

Even if Eskom is managed optimally, its current level of harmful emissions amounts to a breach of human rights, even a crime against humanity (and the environment). This vicious downward spiral of high costs and high levels of toxicity begs the question: What needs to be done to transform energy generation into a virtuous cycle of clean air and clean jobs? Here, most energy experts agree: invest heavily in renewable energy in the course of the next 20 years. The public must also play a crucial role in protecting the environment and becoming more health and environmentally conscious, for instance, by fixing taps and leaks to conserve water, by switching off lights when not needed, by walking or cycling to the shops, and by educating others about reuse and recycling and not pollute drinking water sources. These actions will go a long way to protect our environment, and to ensure healthier lives.

The SASAS dataset collection can be viewed and downloaded here.

The HSRC invites you to attend the upcoming book launch of State of the Nation: Quality of Life and Wellbeing, which is scheduled to take place on 14 May 2024 in Pretoria. Register your attendance here.