South Africa’s social housing programme could help reduce segregation and promote socio-economic mobility by providing low-income individuals and families access to desirable neighbourhoods that are close to jobs, resources, amenities and opportunities. The effects of social housing on upward mobility are not well understood and few mechanisms are in place to measure the programme’s impacts at the household level. HSRC researchers have begun to examine these questions and are leading processes to improve the programme’s contribution to socio-economic transformation in the country. By Jessie-Lee Smith

South Africa has among the highest levels of income and wealth inequality in the world. This is evident when comparing the standards of living between neighbourhoods in South African cities. Since its first democratic election, the South African government has initiated two major housing programmes, first under the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) in 1994 and then Breaking New Ground (BNG) in 2004. These projects emphasised the constitutional right to adequate housing and have resulted in the development of more than three million subsidised RDP/BNG dwellings across the country. Yet millions of families and individuals still live in undignified homes and under conditions of economic precarity.

The mass construction of low-density housing units has amplified neighbourhood inequalities in major cities. This is because the government has tended towards building free-standing houses on cheaper land on the outskirts of cities, which offer less access to resources and fewer economic opportunities. The social housing policy, by contrast, has the explicit aim of reducing segregation and promoting spatial transformation, although the programme has remained a fraction of the size of the human settlements budget. Social housing is subsidised rental accommodation in medium-density apartment blocks, offered to low- and middle-income households. Accredited not-for-profit social housing institutions and private sector companies build and manage social housing projects in better-situated areas with government subsidies and private-sector finance.

Theoretically, social housing allows individuals and families access to otherwise unaffordable urban areas with more economic opportunities and improved social amenities. According to HSRC senior research specialist, Professor Andreas Scheba, social housing specifically aims to bring low- and middle-income people into better-situated neighbourhoods and to address spatial segregation and spatial injustice. “If located in high-value inner-city areas, social housing would mean better employment opportunities, disposable incomes, decreased travel costs, better education and better healthcare,” says Scheba.

Social housing can also allow multiple families to benefit from the same public investment in housing infrastructure. For example, accessible resources and opportunities could promote upward mobility among tenants, which eventually facilitates a movement out of the programme altogether and into private homeownership. In other words, social housing could aid in the alleviation of poverty and social inequality through a “move in, move up and move out” mechanism.

In 2020, HSRC researchers Profs Ivan Turok, Justin Visagie and Andreas Scheba embarked on a project to document the role of social housing in reducing inequality in South African cities. This research was conducted in the face of significant gaps in knowledge and information about past and current social housing developments and their impact. Funded by the Agence Française de Développement through the European Union Research Facility on Inequalities, the project ended in 2021 with a webinar in which the researchers shared their findings with key sector stakeholders – including representatives of the Social Housing Regulatory Authority (SHRA), National Association of Social Housing Organisations (NASHO), National Housing Finance Corporation (NHFC), the Development Bank of Southern Africa, Development Action Group and other civil society organisations, and academics.

A key finding presented at the webinar was that South Africa hasn’t prioritised the release and development of land in well-located areas, leading to a ‘spatial drift’ of social housing projects. “More and more social housing projects are being developed further and further away from inner cities or core areas because of the price [of], and limited access to, well-located land,” Scheba reported. A 2021 report released by the HSRC showed that when subsidised dwelling developments are built away from city centres, inhabitants’ access to jobs, educational facilities, amenities and public services is more limited. Transport also remains a heavy burden on these households, as cost and accessibility often limit their access to certain opportunities.

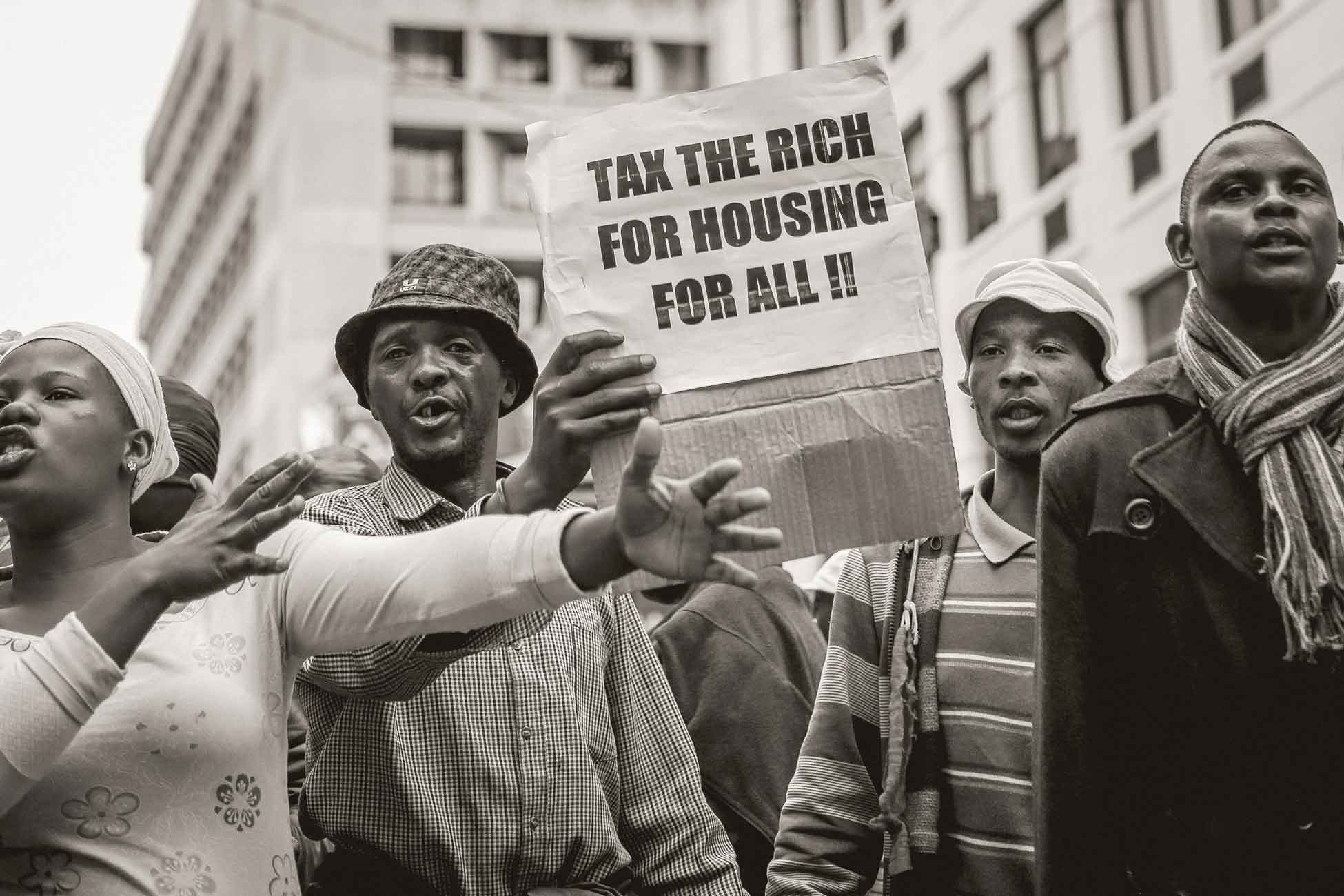

The housing crisis in South Africa has led to numerous protests over the years, with social housing projects having brought some relief. However, were these a means of upward social mobility or are most of them located too far from economic hubs? Photo: Pierre F. Lombard, Wikimedia Commons

Yet, the government owns sizable amounts of land in well-located parts of our cities, with good access to economic opportunities and social amenities. Scheba emphasises that the issue of land is important to highlight because, while there is a lot of pressure on the local and national government to release public land, progress of this release has been slow. “Public land release is a very straightforward way for the government to support the delivery of social housing in our cities,” says Scheba. In 2023, Turok and Scheba led a research project with the Development Action Group, examining how local governments can more effectively release land for social and affordable housing in our cities. The reports will be launched in the first half of 2024.

HSRC researchers also found major gaps in information surrounding ongoing social housing projects. Therefore, they are leading a collaborative process with SHRA, NASHO and others to develop a “social housing portal”, which will provide residents, researchers, policymakers and social activists with an open-access platform to obtain up-to-date information about social housing projects in the country.

This portal will sustain the needs and desires of stakeholders and individuals to access systematic data on all social housing projects across South Africa. “It is clear that key stakeholders, residents and communities are interested in engaging in the discussion, and appreciate public knowledge and evidence,” says Scheba. “The web portal will present data on social housing organisations, information about key social housing institutions, and an interactive map so the public can see where the social housing projects are located in South African cities, how many there are and how big they are.” The integration of population, spatial and socio-economic information will allow for even richer analysis.

A major gap identified by HSRC researchers was information about the success rates of upward socio-economic mobility among beneficiaries of social housing projects. “There is so much demand and effort to just increase delivery of social housing that there isn’t enough attention being placed on what it actually does for tenants and how it meets its own objectives,” says Scheba.

In a recently published study led by Visagie, the team examined the effects of selected social housing projects on social mobility in major South African cities. The HSRC team found that upward mobility was modest and that effects were far more complicated than anticipated. Positive mobility was seen in less than 8% of households, who left social housing for home ownership, and in 14% of households, who moved because of better work opportunities. Other common reasons for tenants to leave social housing complexes were that they couldn’t afford the rent, or for other neutral reasons, such as their relocation to another city. While unfavourable labour markets and wider economic circumstances influence the upward mobility of social housing tenants, researchers also found that social housing institutions and policymakers generally did not give sufficient attention to household upliftment.

“Evidence is patchy and inconclusive, and more systematic research needs to be done,” says Scheba. Public and private stakeholders need to invest more resources into monitoring and evaluating the impacts of social housing on low- and middle-income households. With more research and careful analysis of data, stakeholders will better understand and be able to promote social housing’s contribution to upward mobility in the country.

Research contacts:

Prof. Andreas Scheba, senior research specialist in the HSRC’s Equitable Education and Economies (EEE) division and an associate professor at the University of the Free State – ascheba@hsrc.ac.za

Prof. Justin Visagie, senior research specialist in the HSRC’s EEE division and an associate professor at the University of the Free State – jpvisagie@hsrc.ac.za

Prof. Ivan Turok is an honorary research fellow and former distinguished research fellow in the EEE division of the HSRC. He is also a National Research Foundation (NRF) research professor at the Department of Economics and Finance and the DSI/NRF Research Chair in City-Region Economies at the University of the Free State.