Dominating the informal food sector in South Africa, women play an important role in the country’s agri-food system. An HSRC study shows that women informal food traders experienced the worst of the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, yet received the least assistance. By Sikhulumile Sinyolo, Peter Jacobs, and Matume Maila

The COVID-19 pandemic and restrictive measures to reduce its spread disrupted the agri-food supply chains in South Africa and elevated the vulnerability of informal food traders to business failure. These are small, often owner-operated enterprises, such as street traders, hawkers, spaza shops, and bakkie traders involved in selling various food types. Informal food traders were unable to avoid compliance with COVID-19 containment measures that invariably hampered the ability to source supplies or sell foods to customers. Mandatory cuts in operating hours called for radical adjustments to volumes of food items sold and how traders procured their supplies, such as fresh produce with a limited shelf-life and ingredients for prepared foods.

Enterprise closures and job losses as a direct consequence of COVID-19 were not equally spread and felt across the informal and formal sectors, and between male and female traders. For example, a publication by the Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing network estimated that 3.5 times more jobs were lost in the informal than in the formal sector, and reported that while 23% of men in the informal sector lost their jobs, 29% of women in this sector did so.

The plight of informal food traders was worsened by the government’s apparent neglect. In a paper published by Food Security in the early months of COVID-19, Dr Marc Wegerif, a lecturer at the University of Pretoria, argued that the government had ignored the needs of informal food traders, showing limited knowledge of the sector’s importance, as well as negative feelings towards it. Local authorities and policing agencies who enforce the bylaws and rules that govern the informal food trade in public spaces overzealously implemented restrictions that halted their trading activities. Wegerif called for a more nuanced appreciation of the informal food trade, arguing that these vendors are crucial in localising the consumer end of agri-food value chains.

Women make up a substantial proportion of informal food traders, but are more likely than men to suffer adverse outcomes, due to structural, social, institutional and administrative biases. These disparities were laid bare during the early phase of the pandemic. A recent paper by the HSRC sheds light on the experiences of women engaged in the informal food trade in South Africa during the early waves of the pandemic, drawing on a purposive survey of 804 informal food traders conducted in July – September 2020. This rapid exploratory assessment aimed at understanding the early impacts of the pandemic and measures implemented to control its spread.

Photo: Neo Nthime, Wikimedia Commons

Gendered informal food-trading activities

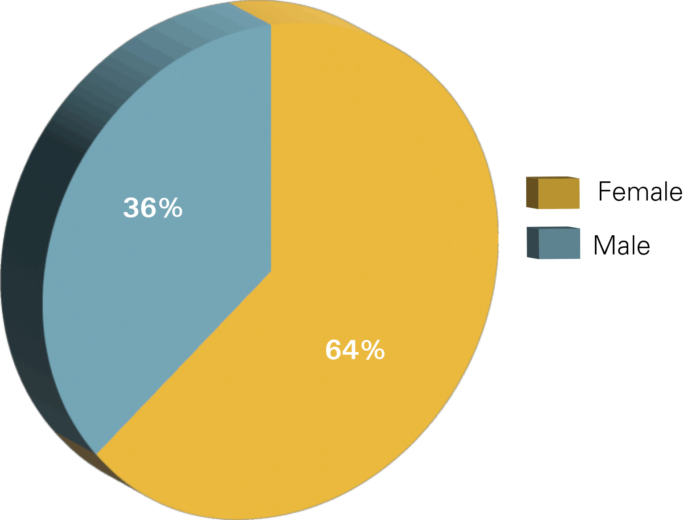

Three categories of informal food traders were targeted: fresh fruit and vegetable traders, cooked/prepared food sellers, and connecting (bakkie) traders. Most of those who were interviewed were female (Figure 1), providing further evidence that women dominate the informal food sector in South Africa.

Figure 1. Gender composition of informal food traders

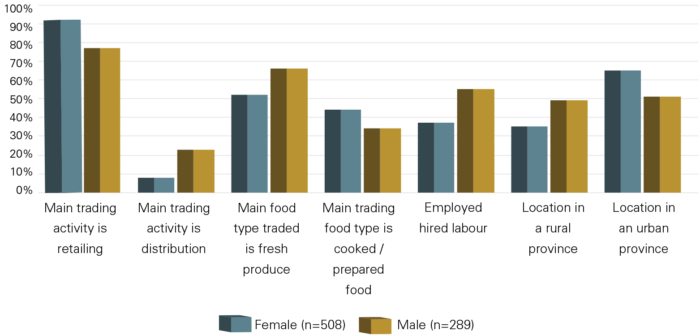

Figure 2 presents characteristics of the informal food traders by gender. It shows that women were more likely than men to be involved in informal food-retailing activities (as stallholders or hawkers), by trading prepared, processed or cooked food, and operating in urban provinces (like Gauteng and the Western Cape, where more than 50% of the population resided in urban areas in 2019). In contrast, men were more likely than women to operate as informal distributors (‘bakkie traders’), selling mostly fresh produce (e.g. fruit and vegetables), in rural provinces (like Limpopo, KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape, where less than 50% of the population resided in urban areas in 2019). More than half of the male traders (55%) employed hired labour, while only 37% of female traders did so.

Figure 2. Characteristics of informal food traders by gender

Gendered COVID-19 and lockdown impacts

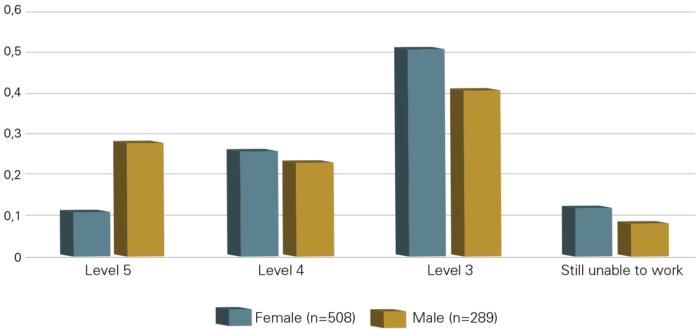

Figure 3 shows that despite the food sector being considered essential, many informal food traders were unable to operate during lockdown levels 4 and 5, with most only able to operate since level 3. It shows that lockdown measures affected female- and male-owned enterprises differently: during the level 5 hard lockdown, only 11% of the female-owned enterprises were able to operate, while 28% of male-owned enterprises did so. While this gender disparity was smaller during level 4, it was only during level 3 that female-owned enterprises were able to catch up with their male counterparts.

Figure 3. Lockdown level when informal food traders were able to operate, according to gender

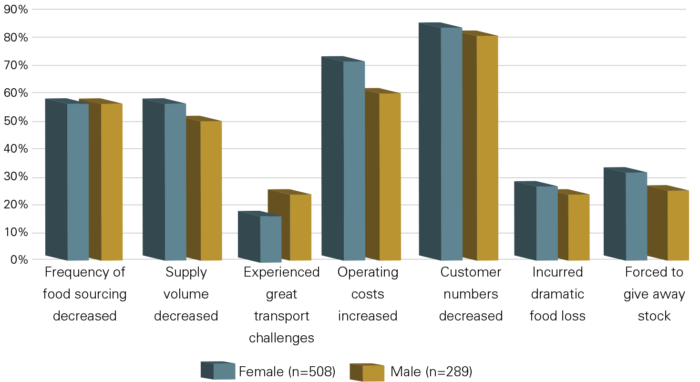

Figure 4 shows that informal food traders experienced challenges with regard to supply logistics, operating costs, customers, and food loss; these differed between male and female traders, with the latter showing higher vulnerability across most of the dimensions. More female traders were negatively affected and experienced decreased supply than male traders; also, a marginally higher proportion of females than males experienced decreasing customer numbers, a statistically significant difference. As numbers of customers declined, especially during lockdown levels 4 and 5, some traders reported losing their stock or giving it away, with more female than male traders experiencing dramatic food loss due to limited demand. Changes in customer purchasing patterns, major employment losses, and reduced wages may be reasons behind this decrease in products purchased. Figure 4 demonstrates that female-owned enterprises, which rely mainly on localised food sources, fared better than males when it came to transport and cost challenges.

Figure 4. Gendered COVID-19 and lockdown impacts on supply, transport, costs, customers and food loss

Informal food traders’ gendered access to support

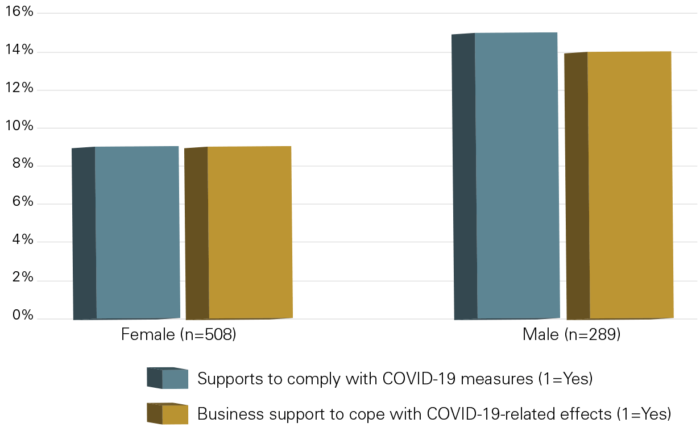

Figure 5 shows that a very small proportion of informal food traders (11% of respondents) received any COVID-19-related support, with most receiving no assistance. The situation was worse among females; for example, while 15% of male-owned enterprises received support to comply with COVID-19 requirements, only 9% of female-owned enterprises received such support. A similar pattern ensues in terms of business support to address the effects of the pandemic; however, during the COVID-19 lockdown, women informal food traders who did not receive business support implemented measures to keep their businesses afloat. Some traders reported changing how products were traded, reducing employees, and switching suppliers, while others stated that they took loans or had to switch to different products.

Figure 5. Gendered access to support

Implications for agri-food system transformation

This study indicates that women experienced the worst economic effects of the pandemic, and yet received the least assistance. Improving the gender sensitivity of interventions in the agri-food system requires that the role of informal food traders and women in the country’s food system be acknowledged and harnessed to produce inclusive outcomes.

Female-owned informal enterprises have an important role to play in agri-food system transformations, given their importance in the localised agri-food chains. There is a need for targeted support for informal food traders: reviving those that are no longer operational and increasing capacity for those operating below their normal levels. This requires the establishment of an updated information management system that not only includes informal food traders, but also has a specific focus on identifying those enterprises operated by marginalised actors, such as women.

Authors:

Dr Sikhulumile Sinyolo, a senior research specialist in the HSRC’s Human and Social Capabilities research division

Dr Peter Jacobs, a strategic lead in the HSRC’s Inclusive Economic Development research division

Matume Maila, a PHD intern in the HSRC’s Inclusive Economic Development research division