Glenda Kruss, Human Sciences Research Council and Moses Sithole, Human Sciences Research Council

The ‘one good thing’ caused by COVID-19, according to a recent Harvard Business School publication by Hong Luo and Alberto Galasso, is that it has catalysed innovation. This is apparent in South Africa too, where businesses are introducing changes to mitigate the risks of the pandemic. They are adjusting their practices and strategies, introducing new technologies, products and designs, and determining how they can use digital and automated technologies.

But will they last?

The country’s Centre for Science, Technology and Innovation Indicators, with the Department of Science and Technology and Statistics South Africa, has released the latest national business innovation survey. The survey helps to answer critical questions facing business leaders, industry groups and government policy-makers. The data can help the country’s understanding of the innovation taking place in businesses, so that more firms can be encouraged to innovate. The survey covered the period 2014 -2016.

How innovative are South African firms and what types of innovation have they implemented?

The survey found that innovation was pervasive across all sectors, but particularly in engineering and technology, manufacturing and trade. A high percentage – nearly 70% – of South African businesses were innovation-active. This meant that they had taken some scientific, technological, organisational, financial or commercial steps towards implementing an innovation. The proportion of innovation-active businesses compares favourably with trends in OECD countries.

But, to respond to current challenges, it is critical to understand what kinds of innovation firms are able to implement, and whether the kinds of benefits that result from them can contribute to business strategies and to inclusive and sustainable growth.

What types of innovation have firms implemented?

Innovation surveys typically measure four types of innovation. These are product, process, organisational and marketing.

The survey found that there were distinct patterns of these types of innovation in different economic sectors.

For example, mining and utilities businesses reflected low levels of innovation. For its part, manufacturing had the largest proportion of businesses with product innovation (59.8%) and marketing innovation (43.4%).

Process innovation was most prominent in logistics businesses (61.7%). More finance (52.0%) and manufacturing (49.1%) businesses reported organisational innovations than businesses in any other sector.

Each type of innovation requires specific forms of support.

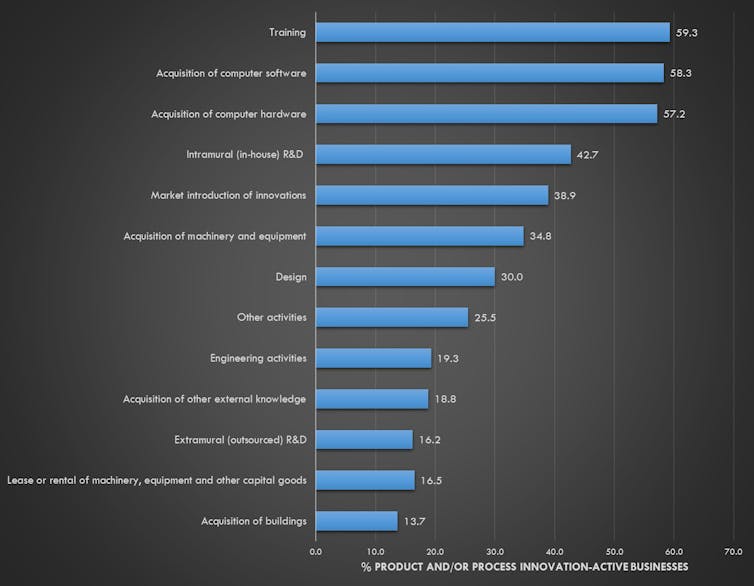

Businesses most typically invested in innovation activities that helped them to prepare for technological and organisational change. They did this by training their workforces and investing in new information technology capabilities (Figure 1).

For both the industrial and services sectors, the biggest-ticket item of innovation spend was the acquisition of machinery and equipment.

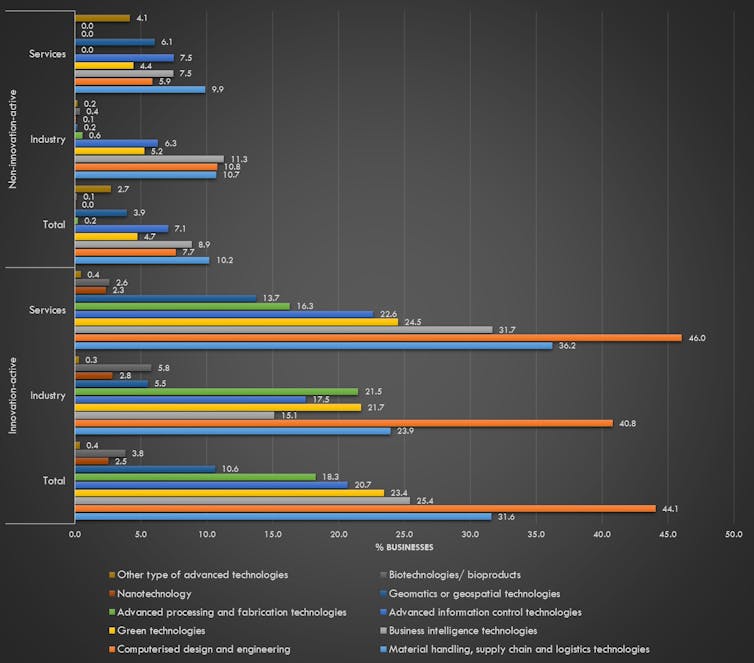

A substantial number of innovation-active businesses reported the use or development of advanced new technologies. These included computerised design and engineering, material handling, supply chain and logistics technologies, business intelligence technologies, and green technologies (Figure 2).

These innovation capabilities suggest that there is a foundation for promoting more innovation that can lead to more positive economic outcomes.

The benefits

Innovation was less likely to have an immediate impact on turnover, and was far more likely to be incremental than radical.

Innovations with high degrees of novelty, such as new to the market or to the world products, did not have a strong effect on the turnover of the businesses that reported product innovations. So, just over 80% of their turnover was generated by goods and services that were unchanged or marginally modified. This was in contrast to a product that was new to the market (10.8%), new to the business (7.0%), or new to the world (1.8%).

Quality improvement was the top-rated innovation outcome for innovation-active businesses. Improved quality of goods and services was considered by 38.0% of product and process innovators as a highly successful outcome of innovation. This was followed by increased revenue (31.8%) and improved profit margins (30.9%).

Similarly, for nearly 50% of organisational innovators, improved quality was the main innovation outcome.

Entering new export markets – or increased export market share – as a highly successful innovation outcome was reported by only 7.5% of product and process innovators.

Innovation-active businesses also accessed national and global markets more than their counterparts with no activity. This included markets in the rest of Africa, Europe and Asia. Businesses with innovation activity were more likely to have sold their goods and services on national markets (58.1%), when compared to non-innovation-active businesses (37.7%).

Firms that were not innovation active were more restricted in their reach. They accessed selected provincial markets (57.4%) more than any other market.

The challenge is to grow the scale and range of types of innovation, to ensure that such outcomes and benefits are more widespread across more sectors and businesses.

Solutions

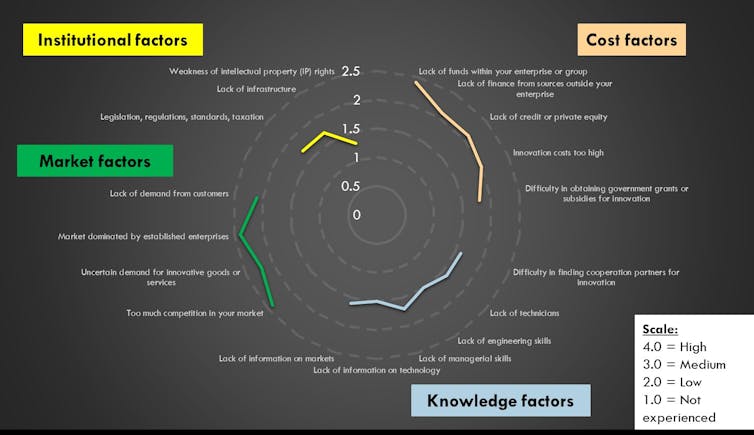

Businesses’ perceptions of the barriers to innovation were grouped into four sets of factors. (See Figure 3.) These provide critical insights into potential spaces for intervention.

The most significant barriers relate to market factors. These include market dominance of established firms, too much competition, and uncertain demand. For non-innovation-active businesses, the most widely reported barrier was a lack of demand for innovation.

To address these barriers requires stimulation of new and expanded markets. In the South African case this requires structural economic reforms. There are a number of steps government can take. It can, for example, ensure that regulatory conditions are more conducive for creating new businesses. It can also improve the transport and communication infrastructure.

Government also has an important role in stimulating demand in the context of the economic, social and health challenges of COVID 19.

Cost factors were also significant. These ranged from the costs of innovation being too high, to lack of funds for innovation within the business or from external sources such as government or private equity.

The vast majority of innovation-active businesses relied on their own funds to innovate (77.0%). Only 1.7% relied on government as a source of funds.

This points to the fact that public sector funding can be targeted more effectively to stimulate innovation. Examples include the new Sovereign Innovation Fund proposed in the 2020 budget or the R&D tax incentive.

But it’s equally important to create conditions that make private equity funding more attractive.

Knowledge factors were not as significant. Nevertheless, strengthening the link between innovation and skills development strategies would be valuable.

Institutional factors, such as legislation, regulatory and intellectual property rights frameworks, and infrastructure were not perceived as significant barriers.

Way forward

In local, national and global contexts, rapidly advancing digital technologies and their applications have opened up the space for innovations as yet unimagined in products, processes, marketing and organisation.

The evidence from the business innovation survey is an invaluable opportunity to reflect on where South Africa’s innovation strengths and challenges lie. It also opens the door to interrogate how existing policies and funding mechanisms can be used more effectively to facilitate business innovation in the country.

Glenda Kruss, Executive Head of the Centre for Science, Technology and Innovation Indicators, Human Sciences Research Council and Moses Sithole, Research Director, Centre for Science, Technology and Innovation Indicators, Human Sciences Research Council

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.