MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS 2016

Speculation is rife that the ruling party has lost some of its appeal among South Africans, many of whom have grown frustrated with waiting for the promises of a “better life for all”. According to some analysts, disillusionment with the ANC has gradually been building over the past few years, with people generally feeling that the ruling party is out of touch with the hardships of ordinary citizens. As a result, analysts have ventured that alignment or “feelings of closeness” to the ruling party has been diminishing. In this article, Jare Struwig, Stephen Gordon and Benjamin Roberts explore alignment with the ruling party over time and also how it compares with other parties.

Data from the South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS), an annual cross-national opinion survey was used in this study. The SASAS sample is 3 500 adults aged 16 years and older living in private homes. Most rounds of the survey are conducted between October and December of each year and all questionnaires are translated into the various major languages of the country.

Prior to the last four elections in South Africa, the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) conducted a Voter Participation Survey (VPS) on behalf of the Electoral Commission of South Africa. The VPS is a nationally representative, cross-sectional survey that is conducted between six to nine months before an election and consists of a sample of 3 500 respondents. The aim of these studies is to examine the political landscape prior to an election and also to determine factors that might impact voting behaviour. One of the themes explored in the VPS is unfulfilled expectation and what South Africans would do if the political party they voted for did not meet their expectations. In this article the loyalty of South Africans are explored by Jare Struwig, Ben Roberts and Steven Gordon.

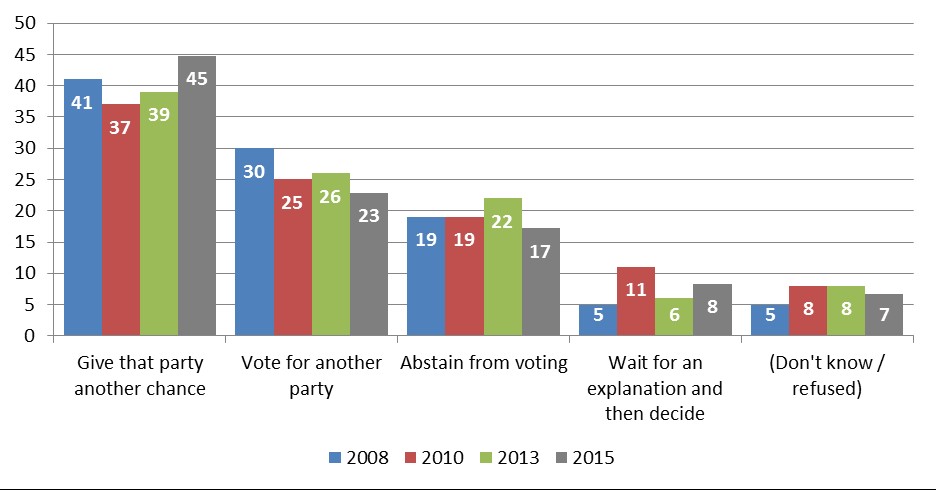

As a means of assessing how South Africans would respond in a situation where the party they voted for in a previous election failed to live up to their electoral promises, respondents were read the following statement: “If the party you voted for did not meet your expectations, the next time there is an election would you…vote for another party, not vote at all, give that party another chance or wait for an explanation and then decide?”. Results showed that the most dominant answer from South African voters (45%) was that they would give the party another chance.

Source: Voter Participation Survey (VPS) 2008, 2010, 2013 and 2015.

Note: The reported figures are for all respondents 16 years and older, not exclusively the voting age population.

In 2015, less than a quarter (23%) of South Africans indicated that they would switch their vote to another political party on Election Day, representing a decline in the intention of the ‘swing vote’ since 2008, when 30% indicated they would vote for another party. Less than a fifth (17%) said they would abstain from voting.

In 2015, a minority (8%) offered contingent support to their preferred party, stating that they would first evaluate the explanation provided for non-performance against electoral promises before deciding how to respond at the ballot box. When combined, party loyalists and contingent supporters account for more than half (53%) of all responses. More than half of South Africans therefore remain committed to their party of choice. Abstention and vote swinging therefore does not represent the dominant election response to political parties not delivering effectively on their manifestos or meeting the needs of constituents during an inter-electoral period.

As the radar diagram demonstrates, party loyalty is strong among those aged 65 years and older with 63% favouring this response if their the party they voted for in a previous election failed to live up to their electoral promises. Younger people were less likely to prefer loyalty to the party, with approximately two-fifths of individuals in the 16-34 age cohort favouring loyalty as a response to unfulfilled promises.

People residing in Limpopo and the Eastern Cape also demonstrated a preference for loyalty (about three-fifths). People in the Free State were, by comparison, were more inclined to reject loyalism as a response – only 29% selected loyalty as their preferred choice of action. Among South Africa’s racial minorities, less than a third of white and Indian South Africans favoured loyalty as a response and only 38% of coloureds said they would remain loyal to their party of choice.

Note: The reported figures are for all respondents 16 years and older, not exclusively the voting age population.

Source: Voter Participation Survey (VPS) 2015.

There appears to be a distinct educational gradient to responses to the question on unfulfilled election expectations. The more educated the respondent, the less likely they are to express a preference for remaining loyal to the party in the face of unfulfilled expectations. Among the Indian minority in South Africa, the share expressing party loyalty is overshadowed by the share of vote switchers or ‘floating voters’.

Also worth mentioning is that abstention is a more common response than switching one’s vote for members of the coloured racial minority. In terms of those who indicate that they would punish their party by abstaining from voting, the highest proportional shares are observed in Free States (36%), a response not found in other provinces.

As a follow-up question, respondents were asked what they would do if they felt that they could not vote for the political party that they typically support. With the option of voting for the same party removed from the range of political choices available, around two-fifths of respondents said they would nominate abstain from casting their vote, or to switch party allegiance (46% and 38% respectively). A nominal share (4%) would deliberately spoil their ballot paper, with a more significant proportion of the voting age public (13%) uncertain about how they would respond.

Note: The reported figures are for all respondents 16 years and older, not exclusively the voting age population.

The highest proportions of abstainers lived in Limpopo (60%), the Free State (54%) and KwaZulu-Natal (52%). Interestingly, people in Gauteng and the Northern Cape would be more likely to vote for another party. In no other province did vote switching overshadow abstention as a preferred response to this question. Many students more willing to identify themselves as ‘floating voters’ if faced with the inability to vote for the political party that they typically supported. Almost half (45%) of adult students said that they would pursue this strategy compared with 36% of students who reported that they would abstain. Switching the party one votes for is most common among Indian respondents (46%) than black Africans (39%), coloureds (36%) and whites (27%). In comparison to younger adults, older South Africans were more likely to favour abstention if they could not vote for the political party they typically supported.

Note: The reported figures are for all respondents 16 years and older, not exclusively the voting age population.

Source: Voter Participation Survey (VPS) 2015.

Going into the 2016 local government elections it is clear that South Africans generally remain loyal to their preferred party, with more than half of South Africans stating that they will continue to vote for their party or give it another chance in the event that the party did not fulfil its promises. Changing a vote or vote swinging is therefore not a common response from voters at this stage in South Africa, although there is signs that the younger generation are more willing to consider switching votes than older cohorts.