South Africa is a global leader in water innovation. Despite this, and despite the demand for innovations that can help farmers and rural communities to access water, few of these innovations are in operation. At a recent seminar, Water Innovation in South Africa: Mapping Innovation Successes and Diffusion Constraints, the HSRC’s Dr Alexis Habiyaremye spoke about why this is the case.

Increasing water scarcity and the ongoing environmental threat posed by acid mine drainage call for creative innovations to use South Africa’s water resources more efficiently. Yet, locally-devised solutions to water-supply problems already exist, according to the HSRC’s Dr Alexis Habiyaremye. For example, eutectic freeze crystallisation (EFC) offers a long-term solution to South Africa’s acid mine drainage problem.

Speaking at a recent HSRC weminar, Habiyaremye said: “South Africa, being a water-scarce country, has developed a living capacity to conduct research and find very innovative solutions to water-related problems. But in contrast… the diffusion of those innovations is still wanting.”

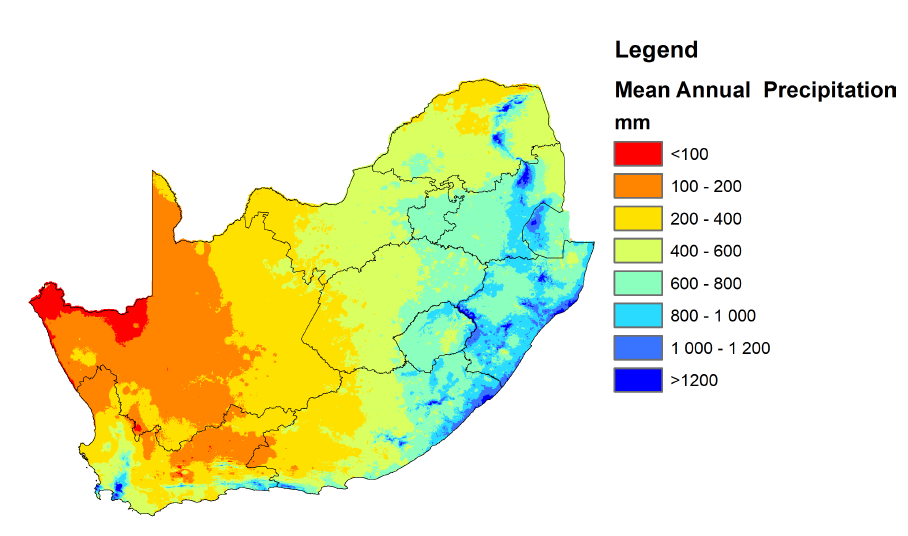

Figure 1: Average annual precipitation in South Africa. Source: Created by Dr Blanchard (CSIR) using annual precipitation data from Schulze, R.E. and Lynch, S.D. (2007).

In a 2018 report, the Water Research Commission identified a number of promising recent innovations that targeted various points in the water supply chain, from sourcing to wastewater treatment.

In addition to EFC technology, these included Aquatrip, an inexpensive leak-detection technology, Arumloo, a microflush toilet that uses only 2.5l of water, thanks to the innovative (lily) shape of the bowel, VulAmanz, a water filter designed to bring potable water to rural areas and AmaDrum, a point of use purification device.

These and other technologies were developed with affordability constraints in mind, Habiyaremye said, and were piloted with subsidies by the Department of Science and Innovation. Despite this, access to water and sanitation remains a critical problem for many communities.

To explore why the technologies were not widespread, Habiyaremye deployed an innovation diffusion model that identifies a series of microeconomic factors affecting the uptake of innovations: these included comparative advantages, financing and adoption costs, context compatibility, and trialability.

Facilitating uptake of innovations It is often assumed that good technologies sell themselves, said Habiyaremye, leading to complacency on the part of innovation agents. “There is a lot of effort that is needed to push people to adopt innovations, even when those innovations are obviously advantageous.”

Jay Bhagwan, an executive manager for Water Use and Waste Management at the Water Research Commission (WRC) spoke about selling an innovation to its intended beneficiaries by making it aspirational. “Which is the best diffusion pathway [for a new technology]?” he said. “Is it sitting on the product, or is it sitting on the offering? If you study the iPad’s diffusion model, it was all on the offering…The money was made on the software and all the platforms that drew you in.”

Other challenges to scale up successful technologies, suggested Shanna Nienaber, another seminar participant from WRC, were systemic in nature. “When you are talking about something that is ultimately best fitted to a public market, it’s a very complex set of constraints…in terms of the rules of the system. How municipalities and water boards, for example, are understanding the rules around single-source procurement…”

Nienaber added that innovations also contend with barriers in institutional cultures, such as risk aversion, and the tendency to lean towards solutions that have been tried before rather than something new.

Local compatibility and ease of use

Innovations that appear successful in small trials sometimes fail to scale up successfully or to work in other settings because of a failure to consider local contexts. The chairperson, Dr Sikhulumile Sinyolo of the HSRC, emphasised the importance of consulting with community members, a philosophy that is embedded in the R-labs approach in South Africa. However, in the case of the water innovations, Habiyaremye’s analysis found that mismatch with local contexts was not the sticking point. The innovations were simple to use and compatible with South African contexts and values.

Nienaber noted that compatibility and ease of use were factors considered early on in the development phase, to ensure that resources were channelled into technologies that were likely to work.

Funding, trialability and industrialisation

Habiyaremye found that despite some government subsidisation, cost remained a prohibiting factor in bridging innovation development and commercialisation. In the case of the EFC technology, a full-scale plant required a prohibitively large capital investment, in the region of R20 million.

In the case of technologies aimed at the household level, even comparatively low-cost innovations such as the Arumloo (±R800), were out of reach to low-income households. For higher-income households, Nienaber said that the low cost of water was a disincentive to invest in water-saving technologies.

In other cases, the technologies fell short in the trialability criteria. The point of use filtration technologies have been piloted in communities, Habiyaremye said. However, for those outside the pilot areas, it is difficult to observe the benefits. A seminar participant commented that, given his own ignorance about the innovations discussed in the research, many South Africans were likely unaware of the available options.

Finally, Nienaber noted, South Africa still had a way to go to industrialise the water sector. “There’s a way to walk still in terms of industrialising the water sector, increasing our manufacturing ability. We’ve made some progress by enshrining water as its own sector in industrial policy action plan over the last few years… It’s more nuanced than just funding.”

Banner photograph (top of page): Children fetching water from stand pipes in Green Point, Khayelithsa. Photo: Masixole Feni/GroundUp (CC BY-ND 4.0)